|

Recently, my husband and I visited the Royal Ontario Museum, commonly known as the ROM, in Toronto, Ontario. The ROM is an amazing place, full of natural specimens and cultural artifacts. You'd need a few weeks to fully explore the entire collection. Because we only had a day, my husband and I decided to focus our attention on the museum's third floor, which features artifacts from many world cultures from prehistory to the 20th Century. As we strolled through the African baskets, eastern Buddhas, Egyptian cat mummies, Grecian pottery and Rococo furniture, I felt inspired and affirmed as an artist. Maybe that's obvious: a trite reaction. But there were two things in particular that I realized in a refreshing and uplifting way.  Greek pottery from the ROM's collection (photo from the ROM). Greek pottery from the ROM's collection (photo from the ROM). The first thing that struck me like a two-by-four was the fact that art, adornment and beauty have been a necessary part of culture from the beginning of time. As an artist/artisan, I sometimes wonder, "What's the point? Nobody really needs the stuff I create." These misgivings were clearly challenged by what I saw at the ROM. Through many ages of history, artists and craftspeople were highly esteemed in all cultures, and their work touched every aspect of life: birth, work, celebration and death. Artistic items like beads and jewelry were sometimes used as currency. Jewelry and decorative, artistic detail in clothing have been part of every world culture as soon as people could work metal and weave fabric. In other words, art has always been integral to life. In fact, without art, the ROM would have very few cultural artifacts, and we would know very little about the people who came before us. The second affirmation I experienced during my visit to the ROM was that upcycling and repurposing are age old practices. People have always used the everyday objects around them to create art, clothing and jewelry. I saw jewelry made from the garbage and trifles of ages past: bone, seed pods, animal teeth, stones, scraps of leather and wood, tiny pieces of shell. Feathers, fur and hair were incorporated into art, masks and even weapons. I think it's only since industrialization that people have had the "luxury" to waste. We can learn a lot from the multitudes who lived before industrialization about finding practical and beautiful uses for scraps and shards. I've always thought of my efforts in upcycling as being mindful of the present and future, but now I see they're also deeply connected to the past.

0 Comments

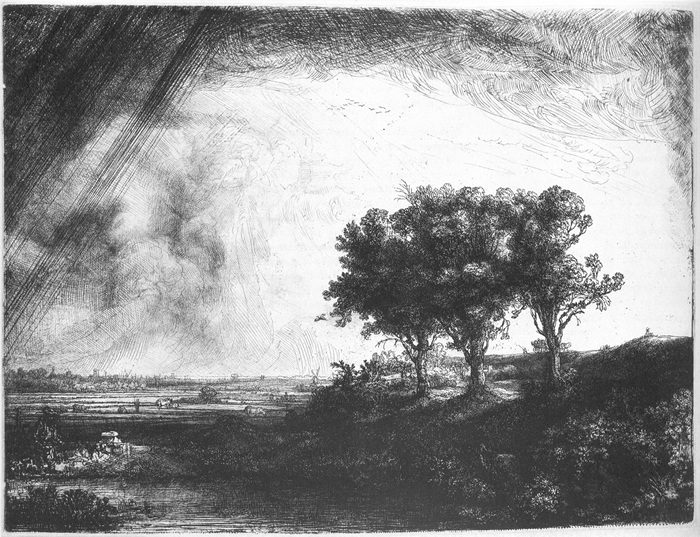

some of Rembrandt's self-portraits: (l-r) 1629, 1635 (with his wife, Saskia, depicting a scene from the prodigal son parable), 1640, 1661

photos, WebMuseum This post is part of my series about the artisans whose work you'll find in The Mennonite Central Committee's Ten Thousand Villages shops. You can read my original post introducing the series here. Today, let me introduce you to Phontong Handicrafts, an artisan cooperative in Laos. Phontong Handicrafts gives people living in remote villages the opportunity to earn a living without having to leave their homes for larger cities to seek employment.  Laos is situated in a part of the world that has been turbulent for several decades. And the country itself has not been insulated from turmoil. From the mid 1950's to mid 1970's, Laos was embroiled in civil war, further complicated by the Cold War and the war in neighbouring Vietnam spilling over Laotian borders. A tense stability ensued when a Communist government took power in 1975. By this time, many Laotians had been displaced from their communities to settlements near larger cities, and employment was difficult to find. These circumstances drove a woman named Kommaly Chantavong to action. As a child, Kommaly had fled from northern Laos to the settlement village, Phontong, near the city Vientang. As an adult during the time of transition as the Communist party took power, she and countless others had difficulty finding work. Kommaly knew that, like her, many women displaced from northern Laos had learned traditional weaving techniques from their mothers and grandmothers: these skills could provide a source of income. In 1975, she gathered a group of 10 women, and together they formed "The Phontong Weavers".  photo, Ten Thousand Villages photo, Ten Thousand Villages The women began by selling their creations at a local market. In 1977, their beautiful work caught the government's eye, and The Phontong Weavers were commissioned to weave the ribbons needed for army and police uniforms. The extra business allowed the women to expand their group to be a cooperative representing other villages around Vientang. In 1985, the weavers applied to the government to become a recognized cooperative, registering as "The Phontong Handicraft Cooperative". The government sold raw materials and dyes to Phontong Handicrafts and then purchased the cooperative's products for resale in the government store and export to Eastern Block countries.  photo, Ten Thousand Villages photo, Ten Thousand Villages It wasn't long before changes in the world would once again result in changes for Laos. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the resulting global economic shifts, trade arrangements changed for Laotian cooperatives. The country's Communist government gradually decentralized economic control and encouraged private enterprise, which entailed that cooperatives would oversee their own transactions. As ever, Phontong Handicrafts was proactive, and established trade arrangements with two fair trade NGO's, including Ten Thousand Villages. Today, Phontong Handicrafts represents over 450 artisans in 35 villages, and now includes wood carvers in addition to fabric and basket weavers.  photo, Ten Thousand Villages photo, Ten Thousand Villages What inspires me about this story is that Phontong Handicrafts has survived - and even grown - through times of great change. They approach their business with the dignity they encourage in their artisans. And their role in Laos remains critical. Subsistence agriculture accounts for 80% of the employment in Laos, when only 4% of the country's land is arable. In this precarious economic reality, Phontong Handicrafts promotes some sustainable employment opportunities while fostering longstanding creative traditions. Thanks to them - and Ten Thousand Villages, of course - people around the world can enjoy beautiful art forms that have been taught in Laotian villages for centuries. 5/17/2013 Women in Rural Bangladesh Find Fair and Sustainable Employment Through CORR - The Jute WorksRead NowThis post is part of my series about the artisans whose work you'll find in The Mennonite Central Committee's Ten Thousand Villages shops. You can read my original post introducing the series here. Today, let me tell you about CORR - The Jute Works from Bangladesh. If you type "Bangladesh" into Google news search right now, most of the stories that come up are about the April 24th collapse of a building that housed several garment factories in a suburb of Dhaka, the capital. Over 1,100 people died in the accident. This tragedy occurred only five months after a fire in another Bangladesh garment factory killed 112 workers. Any catastrophe that involves losses of life and injuries is a tragedy: what's unspeakably awful about these tragedies is that they wouldn't have occurred if the international clothing brands who operate the factories would have properly maintained the facilities.  Jute Bag Made in Bangladesh by a CBJ artisan Jute Bag Made in Bangladesh by a CBJ artisan Of the limited amount of information I know about the economics of the clothing industry, I have heard the argument that improving the wages and conditions for workers in factories like these tragedy-stricken ones in Bangladesh, would upset local economies where the factories exist. I've always suspected that this is an over-simplification (and at worst, a cop-out), and my recent discovery of CORR artisans at Ten Thousand Villages proves my suspicions aren't too far off. CORR - The Jute Works (CJW) describes itself as a women's non-profit handicraft marketing and exporting trust. It was founded to help impoverished rural women in Bangladesh find means to earn a living using local materials they can easily access, like grass, bamboo and clay. Partnering with CJW means women don't have to leave their families to earn income: they can work from home and still raise their children and be part of their communities.  terra cotta garden planter by CBJ artisan terra cotta garden planter by CBJ artisan The artisans are organized into self-governed cooperative groups, and CJW's Education Team provides assistance as needed. Currently, CJW has 220 cooperative groups representing over 4,800 female and 160 male artisans across Bangladesh. That's a lot of people. The artisans make everything from clay and terracotta pottery to jute bags and baskets to handmade paper. CJW looks after exporting the products and also provides funding and support for further education and business ventures for the artisans. This is great news about Bangladesh, and I wish it was a top story. It's hard to be an informed and responsible consumer. Labels don't tell us much, and it's hard to know which corporate responsibility statements to believe. One sure way to buy responsibly is to purchase from organizations such as CJW, who try to nourish sustainable and just employment in their corners of the world. It might seem like a drop in the bucket, but it's something. * all photos courtesy Ten Thousand Villages - click on the images to purchase directly This is the view right now from my studio window. It doesn't get much better than this.

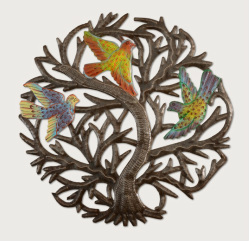

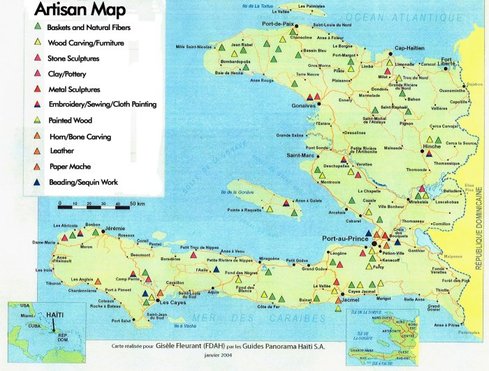

You know how sometimes you get so inspired that you can hardly contain it, like you want to burst? That's how I felt when my sister-in-law forwarded me a little video about a youth orchestra in Paraguay that plays instruments made from trash. They call themselves the Landfill Harmonic. The group is based in the town of Cateura, which is - in essence - built on a landfill. Many people make their living by scrounging through the trash to find things they can sell and recycle. The town is plagued by crime and drugs, and more than 40% of the youth don't finish school because their parents need them to work. In this dereliction, the Landfill Harmonic is a hope-inspiring creative outlet for the kids who call Cateura home.  Maria, a member of Landfill Harmonic A documentary about the ensemble has been in the works for a couple years, and the film's trailer has been gaining popularity on web and media outlets. And today - April 1, 2013 - the Landfill Harmonic began a campaign to raise funds to take the youth orchestra on a world tour. You can find out more about the campaign - and hey, even donate - by visiting the Landfill Harmonic movie site. I could write a lot more, but really, the video says it so much better than I ever could. You'll be amazed by how beautiful scraps of tin and an old oil drum can sound. Have a look and a listen, and prepare to be mind-blowingly inspired.  "Tree of Life" made from recycled oil drum "Tree of Life" made from recycled oil drum One of my favourite places on earth to shop is Ten Thousand Villages. It's rare that I can walk by a store and not go inside. Ten Thousand Villages is a program of The Mennonite Central Committee, and its chief aim is to provide "opportunities for artisans in developing countries to earn income by bringing their products and stories to [other] markets through long-term, fair trading relationships". I have enormous respect for the MCC and the Ten Thousand Villages program, and I can't say enough about the wonderful things they sell. So, each month on my blog, I'll feature one of the artisans or artisan organizations Ten Thousand Villages represents.  map of Haiti showing the locations of CAH-supported artisans map of Haiti showing the locations of CAH-supported artisans Haiti is not an easy place to live. Violence and political instability are constant, and a staggering 80% of the country's population lives below the poverty line. Adding enormous insult to injury, the catastrophic earthquake in 2010 left over a million people homeless and completely devastated the economy. Since 1973, Comité Artisanal Haitïen (CAH) has worked to encourage Haiti's rich artisanal heritage by helping artisans develop their businesses and find local and foreign markets for their products. CAH represents over 200 artisans in various craft traditions, including stone carving, metal sculpture, paper maché, horn and bone, basketry and natural fiber weaving. The partnership between the artisans and CAH generates incomes to support approximately 1,800 people. Since the 2010 earthquake, CAH has added a new initiative called the Haitian Design Centre, where artisans can generate more designs to ensure the sustainability of their work and income. Talk about amazing.  "Face of the Sun" oil drum sculpture "Face of the Sun" oil drum sculpture I'm particularly fascinated by the metal drum artisans that CAH represents. The craft is unique to Haiti, and it began in the 1940's in a town called Croix des Bouquets, where all the empty oil drums from nearby Port-au-Prince were dumped. Local artisans reclaimed the waste by refashioning it and combining it with other materials to make beautiful art. Because of the artists' resourcefulness with steel drum waste, Crois des Bouquets is no longer littered with steel drums, and the artists now purchase used drums to create their art. There's something very poignant about artists making beautiful art out of rubble in a country with a worldwide reputation for being a political and economic mess. As Haiti struggles to rise from the ashes, the steel drum artisans' creations are perhaps a sign of hope and strength and promise. *All art images courtesy of Ten Thousand Villages Creativity can be a solitary pursuit. This has always been very true for me because I work best on my own. I need undistracted time and thinking space to tinker through ideas and talk myself through experiments. I'm quite fond of solitude but sometimes it's limiting. Because I interact with my materials and ideas alone, I don't always fully appreciate or notice the wonder and and delight in seeing things come to life.

This week, I had an opportunity to be part of a collaborative creative experience, and it reminded me of the value of making things with people. It also amplified my excitement for upcycling. My dear friend, Diana, had invited me to lead a workshop at her church about making upcycled jewelry. She attends a weekly women's group at Community Christian Reformed Church in Kitchener, Ontario, and they came up with a great idea of running workshops for the attendees on a variety of topics for a couple weeks. Eight lovely women attended my workshop. I showed them how to make t-shirt yarn, and then we made t-shirt necklaces together. To get the ideas flowing, I showed them some photos of cool t-shirt necklaces and I brought along some examples of the t-shirt necklaces I have made. Other than that, I provided very little guidance and just let them run with it. It was amazing to see the variety in what these ladies came up with. A couple of them said, "I'm not creative at all", but they proved themselves wrong. I was so engrossed in what we were doing, that I forgot to take photos . . . bummer. So you'll have to take my word for it that they each came up with something totally unique and fabulous. Some sewed beads and buttons onto the t-shirt yarn, some strung the t-shirt yarn with beads and washers I had stolen from my husband's workshop, and others layered different colours of t-shirt strands together. The ladies were pretty stoked about discovering that old t-shirts have a fun - and better - use than old rags or thrift store donations. As we sat around the table working on t-shirt necklaces, they talked about other things they could make with t-shirt yarn, like scarves or headbands for their kids. As I saw their curiousity and interest ignite, I was reminded of what a joy and a privilege it is to create. I was also affirmed in my belief that upcycling is not just for architects, designers or artists: it's something anybody can do, and it's super duper fun.  Today in Canada, we say good-bye to the humble penny. I think a lot of people are probably happy to say farewell to this piece of copper (or copper-plated zinc or steel since 1997) that clutters up our wallets, gets stuck in the washing machine and gets swept up with the crumbs and fur balls from the floor.  I feel a little conflicted today. I am one of those people who never had much use for the penny: as a unit of currency it has never made much sense (cents - ha!) to me. It has made the ridiculous .99 prices possible, after all. But the history buff in me - the person who's sad we don't send letters anymore, who loves old stamps and typewriters - is a little sad. It's similar to the sinking feeling I had when the Royal Canadian Mint phased out the one and two dollar bills, but this time it goes deeper. The penny, the one cent, which has been around since before Confederation, will no longer be part of Canadian life. Think about how the penny has been part of our cultural fabric: "a penny for your thoughts", penny loafers, "a penny saved is a penny earned", a lucky penny, throw a penny in a fountain and make a wish, penny sales and penny drives. These will now be things we used to say or do. I think what I'll miss the most, though, is the sense of history you get when you study a penny or run your thumb across its surface. When was it minted? Which maple leaf design does it have? Or is it a 1967 penny with Alex Colville's rock dove design? Is it round or 12-sided? Each one has its own shade of brown patina and history of pocket-dwelling and changing hands.  Maybe I'm being over-sentimental about a little round piece of metal. But, as much as I'll be glad to carry a lighter wallet, there's a part of me that feels sad to lose a piece of history today. |

Details

Jane Hogeterp Koopman

Subscribe to Jane's Blog by RSS or email:

Categories

All

Archives

January 2018

Stuff I love:

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed